On 18th June 2019 the UKIPO and WIPO hosted ‘AI: Decoding IP’: a conference dedicated to the AI zeitgeist in the intellectual property industry.

This post features the introductory comments from Lord Kitchin and Francis Gurry of WIPO, followed by the panel on new business models, and how AI is disrupting IP.

Part Two features (or at least will feature) the afternoon sessions on ownership, entitlement and liability (featuring Prof. Lionel Bently, Dr Eleanora Rosati, Prof. Tanya Aplin and others) and the sesison on ethics and public perception (Dr Christopher Markou and Dr John Machtynger of Microsoft).

Opening Session

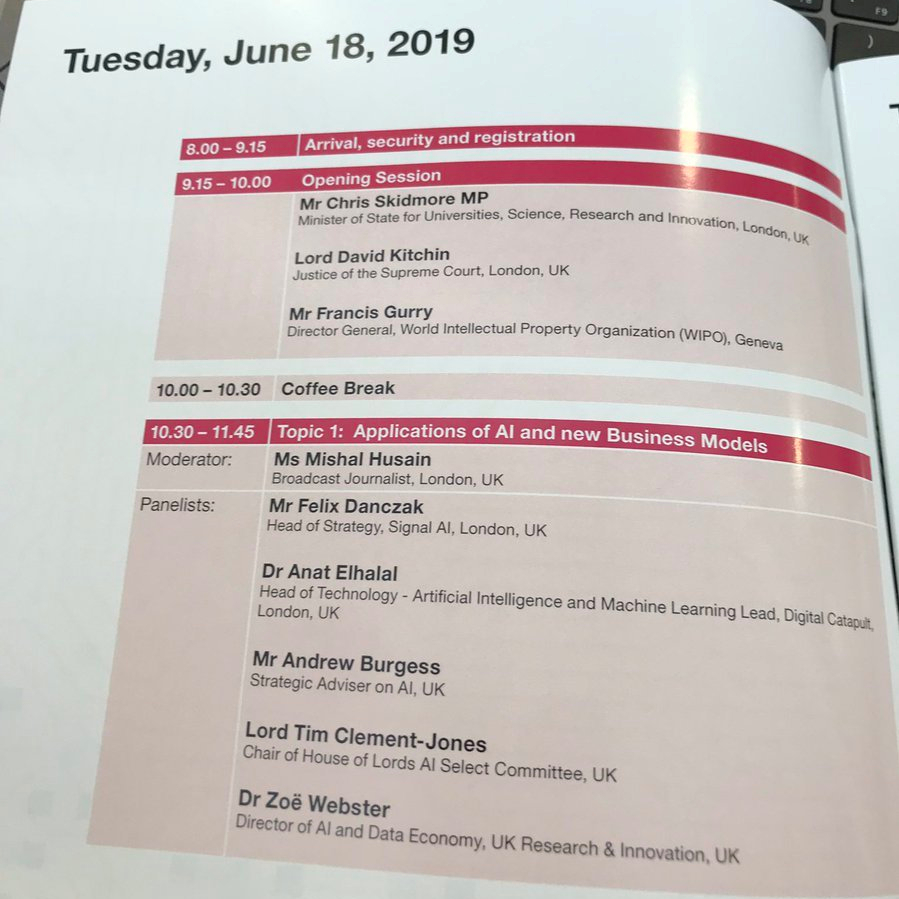

The first session of the day is supposed to be an introductory panel with Chris Skidmore MP (Minister of Universities, Science, Research and Innovation) , Lord David Kitchin (no intro needed), and Mr Francis Gurry (Director General of WIPO).

Mr Skidmore MP however decided he had pressing commitments in parliament. Instead we had a video message praising the “transformative potential” of AI. Chris dismissed the media portrayal of sinsiter AI, and acknowledged the reality of AI as a tool, in particular machine learning. UK government analysis has potential to raise UK GDP by 10%, and so the government is promoting AI innovation.

The government wants to create the best IP environment for AI. The government is publishing two reports on AI. One is on patenting in AI: activity has doubled in last year in the UK, ahead of other jurisdictions. The UK will assess its IP framework.

[Artifical intelligence: a worldwide overview of AI patents <- link to the report, and also the raw data on the patent numbers analysed]

The second report looks at the music industry. Chris talks about the volume of data produced by the creative industries. The IPO commissioned Ulster University to write a practical report looking at the challenges facing music makers. AI is seen as having a key role in helping monetisation of digital distribution for music artists. [Ed: this seems a bit tangential to AI, but sounds interesting]

[Music 2025: the music data dilemma <- link to the report]

Lord Kitchin

Lord Kitchin’s turn: AI has been called the 4th industrial revolution. Prof. Hawking warned of clever machines running amok, and that there was little between a biological brain and a clever machine. Elon Musk has described AI as summoning a demon.

Lord Kitchin says we are already interacting with AI systems in Alexa, Siri, bank fraud detection systems, suggested shopping items. AI will assist in the processes od diagnosis and also in drug discovery. AI may spot helpful information in genetic data. AI may improve productvity in agriculture, and limit work by humans in hazardous conditions.

Lord Kitchin also talks of AI in socail interventions by the state in relation to child welfare and other issues. On the legal system Lord Kitchin acknowledges the role of AI in predicting disputes as well as in producing legal documents.

Lord Kitchin says the AI sector deal is ensuring we are investing in R&D and taking other positive steps to assist creative businesses in these areas.

McKinsey estimates 26 to 39 billion dollars have been invested by the big technology players. The public have however expressed worries about harm by machines and danger to personal data and even free will. Lord Kitchin says that ethical standards will be reuqired on an international basis. The process of decision making must be transparent.

Will we end up attributing personality to robots? Saudia Arabia has granted citizenship to a robot called Sophia (!). Policymakers must take into account all these factors.

What is the role of IP? AI challenges some of our basic assumptions. Lord Kitchin mentions the ‘Portrait of Edward Bellamy’ the first AI artwork sold at auction, making over $400,000 dollars. Should this receive copyright? We must graple with those questions.

AI and patents raise many questions. Lord Kitchin talks about the EPC exclusions and the issues surrounding mathemetical methods and computer implemented inventions. There are also issues under US law, particularly post-Alice.

The IPO in Europe and the US are seeing many filings in life sciences, autonomous vehicles, telecoms and logistics. The US, China and Japan lead the field. The overall picture is one of vigorous research and success in indirect patenting of real advances. But is the patent system falling short?

Should patentability extend to non-obvious advances in the building blocks of AI, regardless of their implementation?

Prof Ryan Abbott (speaking later today) points out that as long ago as 1994 people considered the idea of a ‘creativity machine’ capable of creating new songs based on previous music. IBM’s watson is also cited as a creator. How is obviousness to be assessed in this area? These are fundamental questions.

Traditional notions of inventorship consider human creation. Lord Kitchin is not sure that the same considerations apply to grant of a monopoly for a coputer generated invention. However, we may need to incentivise the creators of the creative computers.

Further, will AI become a powerful tool for the person skilled in the art (in the hands of Sir Robin Jacob’s ‘nerd’) , thereby making many inventions obvious?

Returning to copyright, the EU acquis is very complex. Programs have been protected. But does copyright reside in AI generated works? IBM’s Watson has written a cookbook. AI can also now be used to generate new and better software. Infopaq and other cases impose a standard (Author’s own intellectual creation) that indicates such creations are not protected, contrast that with the UK act that considers computer generated works to be authored by the person who made the arrangement for its generation. Are these provisions applicable to AI? If so, are they compatible with EU law? [Ed: wil it matter in just a few months time? Lord Kitchin avoids the B word]

Lord Kitchin asks if it is time to accept that modern computers and algorithms can introduce elements of originality?

Lord Kitchin asks, ultimately, what are we trying to incentivise?

Francis Gurry, WIPO

Mr Gurry says AI has implications throughout the economic system. Mr Gurry says the fundamental question is: what sort of policy setting will best favour the development of AI innovation?

IP rights have been an efficient but not essential policy tool in the industrial age. Francis points to the WIPO study on AI (link).

That study covered thousand of scientific publications and patents. There was a sharp upsurge in scientific publications in 2003, followed about 10 years later by patent applications.

The upsurge from 2013 in patent applications means more than half the AI applications since 1950 have been since 2013. One third of all AI applications concerned machine learning. There was also robust growth in neural network related patents.

Mr Gurry cautions that there are many aspects of the IP system other than patents. The patent system is a creation of the industrial age but is being used on a widespread basis in the digital age. Copyright and trade secrets are also important: but are there gaps? Do aspects of AI fall through holes in the IP system?

Mr Gurry mentions the issue of authorship in copyright, which he sees as a greater issue than inventorship in patent law. Mr Gurry sees absolutely no value in attributing ownership rights to a machine. Our approach must be consistent with out position on liability.

One practical question is how we will know when a work has been generated by a machine.

Does the nature of AI require new rights or new approaches?

Mr Gurry says this will take us to our greatest challenge: data. This provides the operating conditions for AI. Data then raises questions of personal data, secrecy, security, integrity, ethics and commerce. This is the major policy challenge.

A good example is mdeical data: a 100 billion dollar a year industry in the US. We need innovation in the medical sphere, but ethics in this area is of particular importance.

Mr Gurry says the key question is this: How do we reconcile the need for openness in processing with the need for business to retain some proprietary interest in the way they provide their service.

Nobody is saying ‘create a property right in data’. Mr Gurry cites the laws of Hammurabi regarding property ownership in ancienct babylon [Ed: not in most IP statute books].

Francis points out the issue of lack of international cooperation at a general politicial level. Some leadership is therefore required.

In response to an audience question Mr Gurry says that the term ‘industrial revolution’was only coined 100 years after the fact. There may be time for an institutional response. Will parliament be too slow to recognise change now, which is happening at a greater pace than ever?

Session 2: Applications of AI and New Business Models

The first panel was hosted by the journalist Mishal Husain.

Dr Anat Elhalal (Head of Technology at Digital Catapult) was the first to speak. Technology is moving all the time and we have to adapt. AI might be slightly more compliacted than some other technologies.

Dr Elhalal has some examples of companies that Digital Catapult has helped. Deepzen – Ai speech generation for audiobooks; Cyanapse – Ai solutions to improve human perception of images and data; Scholarcy – a company that generates summaries of text (think auto-flashcards). Iprova are also mentioned (coincidentally they also were represented at the Ikat’s event on the new DSM directive last week) – they deal in machine generated inventions.

In protecting IP a company called blokur is looking at creating a blockchain music rights platform. Of real interest is a system by a company called lobster that helps auto-attribute images and videos posted online. AI is also in use in turnitin plagiarism software.

Next to speak was Andrew Burgess (an independent IP consultant), who sought to break down AI into three objectives to help create a framework for discussion. The first is recognising data – speech and image capture, data extraction from documents. AI is good at taking unstructured data and structuring it, classifying it, or detecting anomalies.

Second, AI can be used to derive intent: what is this data saying? This is common in chatbots, for example. Then you have prediction: whether routes in the car or new molecules.

Third, you have artificial general intelligence. That’s where AI is answering the question – why is this happening? Why is data structured like this? Why is this the best solution to this problem?

Andrew is working with the not for profit, DACS, which collects royalties for artists. Again, a blockahin system is proposed to track the provenance of art. This can [apparently] give artists confidence in gaining reward for their work. Systems can also be used to try and find infringing work on eBay, but excluding legitimate goods like auction catalogues. This requires machine intelligence. This approach then becomes more powerful when using image recognition, including for 3D art works.

Lord Tim Clement-Jones (Chair of the House of Lords AI Select Committee) spoke next, giving a parliamentary perspective. He wants to know how we can ensure public benefit while encouraging innovation. Are the EU’s provisions on database rights fit for purpose? Should there be compulsory creative commons licensing of some data sets?

Lord Clement-Jones spoke about th epossibility of third party certification of AI sytems to assuage concerns about companies of needing to publicly expose how their systems work: could we have a regulator?

Should AI be programmed not to infringe IP rights? Should we be making a distinction between computer and human generated works, in terms of availability of rights, or in term?

[Lord C-J did apologise in advance for the fact he was mainly going to be asking questions rather than providing answers]

Key is the question of dsitribution of benefit: corporations with access to data; or should the age of ip monopolies come to an end? The CMA will have to wrestle with that.

Lord Clement-Jones says that parliament will need led gently and by the hand with regards IP related issues.

Dr Zoe Webster (Director of AI and data economy, UK Research & Innovation) spoke next. Dr Webster mentioned the use of AI to decrease food waste, by seeing which goods are left out in supermarkets, and also how much consumers are leaving of different meals to adjust future portions (!).

Data sharing is again mentioned as vital to development of AI systems One example is wind farms, where sharing of data between operators can help optimise future developments.

UKRI is also leading in AI in legal services. This work will also feature efforts in data sharing.

The Panel’s discussion focussed on the issues with IP in projects between organisations – the issue seems to be that these AI projects all require cooperation between organisations. Big organisations get very nervous about ownership of ensuing IP. There needs to be a better framework for ownership and people need to get IP advice at an earlier stage in development.

The issues in data sharing are particularly difficult for small companies, who may not be able to cope with long periods of negotiation before access conditions can be agreed upon.

The talk turns to how we incentivise investment in Ai technology. Lord C-J considers that limited duration IP rights might be an answer. A member of the audience briefly heckles Lord Clement-Jones describing his views on machine authorship of IP as “ridiculous”.

Session 3: Panel on AI & IP Disruption

First up was Belinda Gascoyne, Senior IP Counsel at IBM Europe. She talked about the disruptive value in AI changing the way we interact with digital devices. This occurs by handwriting and speech analysis. This is being applied across sectors.

IBM considers there is an urgent need for review across jurisdictions. The technology is moving too fact for legislators.

New user interfaces give the impression technology is simple, when it fact it has never been more complicated and expensive to develop. Issues with protection by registered rights will push businesses into the use of trade secrets. There are issues with tarde secrets law.

Contractual terms can ensure flexibility. Protection can be strong as courts reluctant to interfere with agreed terms. [Ed: query whether this is really the case given the issues with recoverable quantum in breach of confidence actions]

Professor Ryan Abbott was up next (Professor of Law and Health Science, University of Surrey). People have been sneaking machine generated inventions into the patent system for ages – made by just combining public information. People are using sophisticated techniques to do this (using neural networks) but who is actually going to complain? The machine is unlikely to speak up.

he poses the hypothetical situation where e.g. 100 million in investment in a new AI system will allow it to invent a new ant-cancer drug. How can we motivate investment in that if it can’t lead to a patent?

Prof Abbott says we shouldn’t just shove this change into our existing laws. We need to think about the role of patent law as an innovation incentive system. If we want investment we need to offer protection. Investing in inventive machines will be rewarding. AI will not own this IP. Ownership should go to the machine’s owner.

“it’s easier to author something than to inventor something; I know that’s not gramatically correct”

The inventive step requirement will change in light of AI. It lends the skilled person greater heft in certain areas of research and development. We already see this in for example, Kasparov starting a chess torunament for humans assisted by computers after he was beaten by Deep Blue.

Next was Daniel Berman of eHealthVentures, speaking on AI and big data in healthcare. A lot of work is needed to derive benefit from the available masses of epedemiological data.

Daniel mentioned the issues in assessing healthcare terminology. Google acknowledges 1% of searches relate to medical symptoms, but too often these searches flag serious conditions that alarms searchers. New services will replace this raw tool with an integrated system of assessing patient symptoms that can better guide patient searches and ‘close the loop’ after treatment occurs or symptoms subside.

Other advances are happening in diagnostics. Example is given of vocal assessments of pulmonary conditions using speech samples.

Dr Ben Mitra-Kahn came to visit from the Australian IPO (Chief Economist). They have been implementing a variety of AI tools.

People have to be careful: people don’t want change, they just want things to get better. In reality, you can’t have one without the other.

Dr Mitra-Kahn says it is ironic that people dealing with AI in reality use python, but everyone in this room is dealing with Ai using powerpoint…

Practically speaking new services can help people access Ip services. This can be as simple as helping people search effectively. Tools can also help people choose their marks more carefully, and also select appropriate goods and services based on past applications. This is great for the 60% of applicants in Australia who self file.

These services use computing power: they are not free to offer. This is an issue for government services. The Australian government are opening up the IPO’s data so third parties can create value.

____________________

Part Two features (or at least will feature) the afternoon sessions on ownership, entitlement and liability (featuring Prof. Lionel Bently, Dr Eleanora Rosati, Prof. Tanya Aplin and others) and the sesison on ethics and public perception (Dr Christopher Markou and Dr John Machtynger of Microsoft).