Everything to do with second medical use patents.

Not because of any fault in the legal reasoning: because the decision came to be made by a Court at all.

If you haven’t yet had a chance to read the Pregabalin Judgment then you can save yourself some time by reading this excellent summary by Darren Smyth of EIP.

This article isn’t going to re-tread any ground. It’s about whether the law relating to second medical use patents is fit for purpose, and whether a Court should really be making these assessments, Supreme or not.

The reason you should care about patenting new uses for existing drugs, even if you’re not a patent lawyer, is because it is the future of healthcare. The industry is inevitably and irreversibly transitioning to finding new uses for familiar compounds, rather than researching novel classes of compounds.

The team at Freshfields say that the Supreme Court’s decision in Warner-Lambert v Acatavis may cause the cost of some generic drugs to drop in the short term, but in the long term:

“the likely outcome is to dampen the incentive to develop innovative new products or expand the range of patients they can be used to treat“.

So why is this happening?

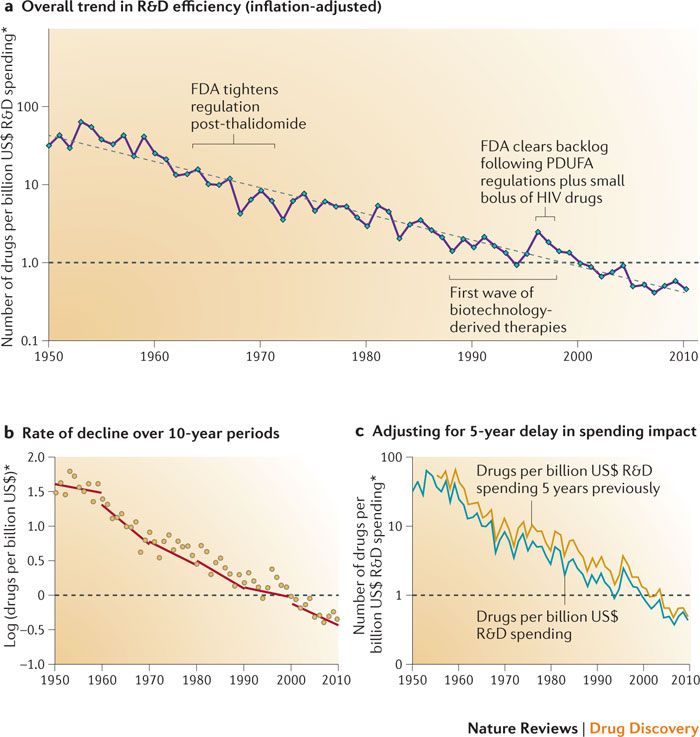

Eroom’s law (which is thankfully nothing to do with digital disclosure) states that the cost and time required for drug development will increase, despite the technological advances being made in the drug development process. The cost for development of a new drug is estimated at $2-3 billion. In contrast, developing a known molecule for a new purpose can cost as ‘little’ as $300m, and takes around half the time (link).

Diagnosing the decline in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency, Scannell et al., 2012,

Nature Reviews Drug Discovery volume 11, pages 191–200 (2012)

Rather than describing new uses as “second medical use”, which perhaps sounds a bit too much like the compound was picked up at a car boot sale, the pharmaceutical industry prefers the term “repositioned” medicines.

The need to provide incentives to companies to explore repositioned medicines is a serious concern. The amounts of money involved are phenomenal: pharmaceutical innovators need certainty that successful new uses will receive protection.

Blockbuster repositioned drugs are already improving quality of life for patients globally. Famous examples of drugs that were successfully repositioned include:

- Sildenafil (a.k.a. Viagra: originally an angina medication)

- Bromocriptine (formerly Parkinson’s disease, then diabetes)

- Minoxidil (also known in the US as Rogaine – previously hypertension and now hair loss)

- Raloxifene (a.k.a. Evista: formerly a contraceptive, then an osteoporosis treatment)

- Zidovudine (Cancer, then HIV)

- Thalidomide (Morning sickness, now leprosy and cancer)

So spot the differences among the above: which effects were deliberate discoveries and which were serendipity?

For Minoxidil and Sildenafil the effects were perhaps fairly obvious.

Bromocriptine and Raloxifene have something in common. While the indications in both cases seem unrelated, there are metabolic mechanisms that link them together. Bromocriptine affects the dopamine system, which in addition to affecting mood, alters the body’s propensity to store and release carbohydrates during the day. Raloxifene affects the body’s natural hormonal system which affects ovulation and also bone density.

Zidovudine and Thalidomide are different. Both were pretty ineffective in their original indication, or had totally unacceptable side effects (incidentally it is a common misconception that the optically pure thalidomide as sold was inherently unsafe: the issue was in vivo enantiomerization into the toxic isomer). In both cases the drugs became library candidates for other therapies and were involved in wide scale screening and assay programs to find new uses.

The future of drug repositioning will rely on much more deliberate research than serendipity. It is perhaps unfortunate that Viagra and Rogaine are such well known examples of repositioned drugs. Combine that preconception with what could be called ‘ambitious’ second medical use patenting on the fringe of existing patent claims, and the result is a lack of recognition of the importance of drug repositioning innovation. This means a lack of recognition that the industry needs assured funding for future development of medicines, particularly for low profit orphan conditions.

The Supreme Court’s Pregabalin decision tightens the belt on innovators: is that the right approach?

Lord Sumption said at [19] of the Pregabalin Judgment that Lord Mance had objected that sufficiency is an area of Judge-made law. Lord Sumption may be right to criticise that statement: Judges are having to apply a single set of principles to a vast range of inventions, claimed in different ways, and they are reaching effective conclusions. The real question is whether the balance between innovator and generic drug manufacturers, and the funding of research into drug repositioning, is something that should be determined by any Judge.

One future issue we need to consider is the effect of computational models of drug discovery on repositioning. Many of these approaches will come close to the use of AI: expect an ardent debate about whether drug candidates discovered by computational modelling using AI deserve patent protection.

UPDATE: 1 December 2018

A friend from the Max Planck sent me a link to this study. By some top researchers from UC, John Hopkins and others it’s a great overview of the developing approach to computational repurposing, written in a very accessible way.

Molecule image credit: Eharlacher91 [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

One thought on “What’s wrong with the Supreme Court’s Pregabalin decision?”