On 13 November 2018 AIPPI held a rapid response seminar on the decision of the Court of Appeal in Huawei v Unwired Planet [2018] EWCA Civ 2344. What follows is a write up of the event – the first part is an analysis of the issues in the case and the arguments on appeal – the second part contains further insight from the hosts into the Judgment and its effect on global SEP and FRAND litigation more generally.

(Part Two is available here).

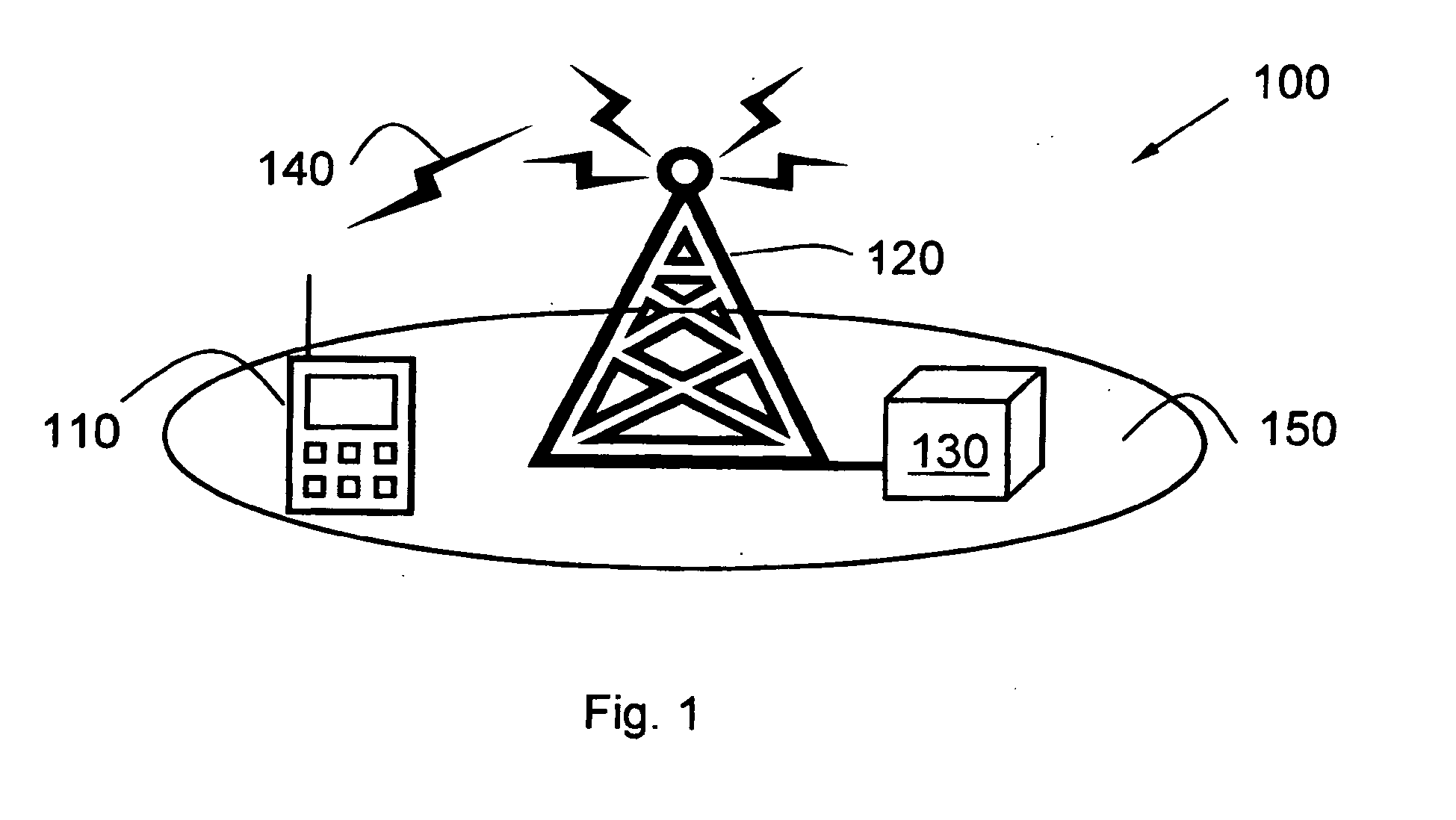

The evening was hosted by The Rt. Hon. Prof. Sir Richard Jacob (UCL) and Richard Vary of Bird & Bird (formerly of Nokia), in response to the handing down by the Court of Appeal of its much-awaited Judgment in the Huawei v Unwired Planet Standard Essential Patent (SEP) Litigation, in relation to 2G/GSM,3G/UMTS and 4G/LTE technologies used in mobile phones.

Introductions

Sara Ashby (Wiggin) provided the introductions and was keen to remind everyone that the AIPPI’s Annual patents round up at Hogan Lovells (hosted by Andrew Lykiardopolous QC) will be on 10 December 2018 (mince pies TBC: Dan Brook of Hogan Lovells to be held responsible)

Richard got us under way by reviewing the background to the decision, and covering off where we stand now: Huawei are apparently intending to appeal to the Supreme Court. For those unfamiliar with the history of the litigation Ericsson sold 50 patent families to Unwired Planet, a US based non-practising entity, who sold 20 of those families to Lenovo and set about monetising the rest.

A number of other implementers having already settled, Samsung waited until the Court door and settled out at an amount believed to be around $10-15m USD (though there is uncertainty about whether this is a recurring payment). Crucially no offer was made by Unwired Planet prior to starting proceedings, in contrast with the commonly perceived requirements for the “FRAND dance”following the Judgment of the CJEU in Huawei v ZTE.

The Story so far

RV reviewed the key areas of the High Court decision by Mr Justice Birss ([2017]EWHC 2988 (Pat)) as follows:

Contract Law

BirssJ’s analysis was one of contractual law, based on the ETSI FRAND undertaking. Birss Jheld:

“(1)As a matter of French law the FRAND undertaking to ETSI is a legally enforceable obligation which any implementer can rely on against the patentee. FRAND is justiciable in an English court and enforceable in that court.”

In Germany the contractual element has not been run, and instead the competition law aspect has been central. Sir Robin was surprised by the German attitude, questioning whether “anyone will take them seriously” if they don’t apply third party laws. Sir Robin was of the opinion that the proper approach is that the law of the third country should be applied unless it is inimical to principles of justice.

Competition Law

As a matter of competition law it was held that UP held a dominant position (this being only assumed, in the absence of a full market analysis) but it was held that UP did not abuse that position.

Key to this finding was that Huawei v ZTE is only a safe harbour, it does not necessarily follow an abuse has taken place if the criteria are not fulfilled: high offers made during negotiation are not an abuse so long as they don’t prejudice the negotiation.

UP was also accused of bundling SEPs and NEPs, but as soon as they were asked for an SEP only license offer they provided one (RV pointed out the fickle nature of opinion on SEP/NEP bundling by stating that in Korea Nokia were accused of abuse for not licensing Nokia SEPs with NEPs)

Sir Robin Jacob expressed his doubts as to the market dominance imposed by essentiality of patents in a general sense: how important is the patent to actually making mobile phones? Sir Robin pointed out that the AG in Huawei v ZTE expressed this principle.

Ed C: Advocate General Melchior Wathelet noted in his opinion in Huawei v ZTE (§§53-58) that the parties had proceeded on the basis of Huawei’s dominant position, and it was not open to the CJEU to proceed on any other basis. He stated:

“I share the view expressed by the Netherlands Government that the fact that an undertaking owns an SEP does not necessarily mean that it holds a dominant position”.

Richard went on to compare inspecting dominance in the FRAND litigation context to looking in the kitchen of the kebab shop on the way home – neither the shop owner or the customer is keen on the idea. Richard said to expect more sustained attacks on the nature of the dominance conferred by standard essentiality, and noted that he was aware of at least two cases in Germany where this had happened. In the present case UP appealed the dominance finding but the appeal was dismissed.

Jurisdiction

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the decision at first instance was that the English Court was willing to set a global rate, albeit only backed up by a UK injunction. This relied on the global nature of the ETSI undertaking, though it was challenged on appeal:

Three Appeal Points

Global or National?

The Court of Appeal found it persuasive that comparable licenses were global in nature and that the portfolio was global. Huawei was selling phones in almost every country in the world.

Huawei alleged that this approach was wrong as a matter of principle given the territoriality of patent rights, but the Court of Appeal agreed with Birss J that it would be impractical to license on a country by country basis. Sir Robin says it has got to be a global license – that it is inherent in the ETSI wording.

One set of FRAND terms?

The most criticised aspect of the decision (particularly staunchly by Judge Robart in the US) arose from Justice Birss’ solution to the Vringo problem: How can the Court give an injunction where the SEP owner has made an offer in the range and the implementer has also given an offer in the range?

Birss J avoided this dilemma by holding that in any given case FRAND was a single set of terms. The Court of Appeal however solved this problem in favour of the SEP owner. Sir Robin says if the patentee has complied with its obligation to make an offer then the promise it has made is fulfilled: “counter-offers have nothing to do with it“.

RV says he thinks Birss J is right, providing as an analogy that there is no conceptual difference to a court under the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 setting the rent for a building. The number set will be a single number. If you have the data for the first 99 flats you could say with almost exact precision the rent for the 100th flat of a block. The only issue is that we haven’t got enough data; so the error bars are currently significant.

Is Non-discrimination hard edged?

What this comes down to is whether Non-Discrimination trumps Fair and Reasonable, or whether it is the other way round. RV says that prior to the Court of Appeal’s Judgment many practitioners saw these terms as caps; that the offer simply has to come under the threshold for each aspect.

The Court of Appeal has however decided that differential pricing is not, in itself, objectionable: if something is fair and reasonable that is good enough. You are not entitled to the lowest rate of any licensor: it is not a most favoured licensee clause. RV says that concept was proposed in the ETSI negotiations and rejected.

The Samsung offer was accepted perhaps because UP was low on cash; Ericsson has also taken potentially low market offers from Apple and Samsung in order to stay solvent: commercial reality is that there will be low comparable licenses. Sir Robin says the Court of Appeal got everything right on this. So what’s the point of the Non-discriminatory bit? Who knows.

The Court of Appeal also discussed the Huawei v ZTE steps that were required for the grant of an injunction, ultimately deciding it was a transitional case given the timing of the two sets of proceedings:

Ultimately Huawei had sufficient notice.

German Courts have generally not regarded steps as mandatory (St Lawrence v Vodafone; however IP Bridge now suggests they may be mandatory).

See Part 2 for the consequences of the Judgment and other FRAND Proceeding: Part Two

This is great, very useful. Thanks Ed.