This is the second part of a series (most likely of three parts) on ethics in intellectual property law. The first part is available here: “is there a role for ethics in intellectual property?“. In this part we focus on biotechnology and biological inventions.

In my last post I wrote about how ethical principles underlie the rights conferred by intellectual property law, and also how they shape the exceptions to those rights, both in relation to patentability, and infringement. More of the same this time round, but with a greater focus on humans, and plants, and micropigs.

In particular I want to look at the following propositions: why you can’t patent something in nature just because you discovered it; why you can’t patent plants or animals; and why some biotechnological inventions are unpatentable because of their effect on human dignity.

I found this fish, why can’t I patent it?

Many reasons. You obviously can’t patent that fish. But why?

Going back to the philosophical underpinnings of intellectual property, one immediate objection comes to mind: there hasn’t been any intellectual labour by the person who found the fish. What have they done to merit the reward of a monopoly?

This concept becomes much more complicated when instead of thinking about a fish, we think about a discovery that does take some intellectual effort, such as the discovery of a new gene sequence.

Article 52 of the EPC states that discoveries as such are not patentable. The EPO guidelines state that this is the case because a discovery in itself has no technical effect and is therefore not an invention. While a helpful legal simplification, this misses half the issue. It ignores the fact that the intellectual labour of the (non-)inventor did not go into creating the article discovered, but into the process of discovery, which may be independently patentable.

Splendid Isolation: Genes

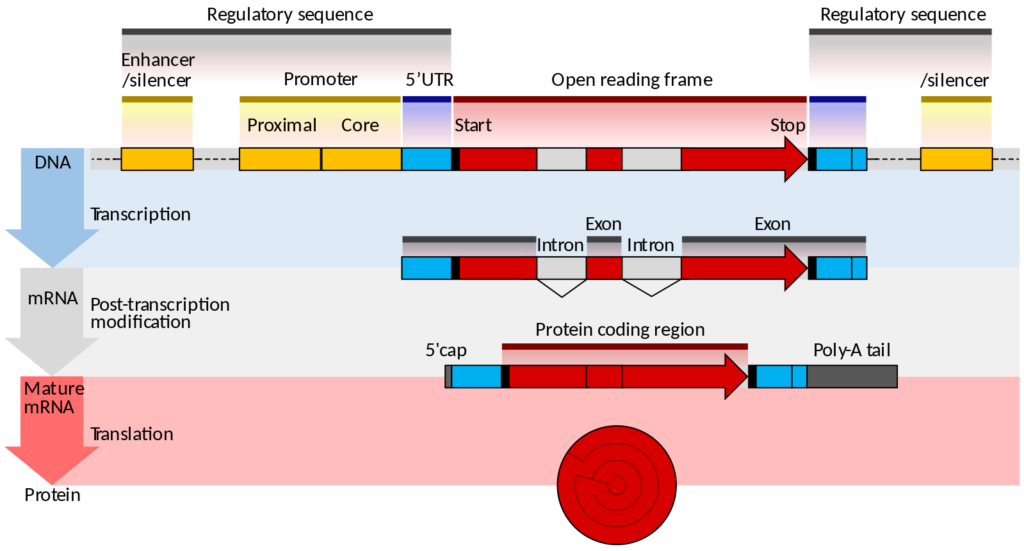

The question of patentability of biological matter is further complicated when we think about the technical work required to isolate biological matter. In the case of a DNA sequence such work might involve finding the sequence responsible for a specific protein, excising it from the genome (and surrounding regulatory sequences) and reproducing it independently from the organism from which it was derived. In doing so non-protein-coding sections of the DNA known as introns may be excised.

Directive 98/44/EC, known as the ‘Biotech Directive’ was published (after ten years of wrangling) on 30 July 1998. It regulates the legal protection of biotechnological inventions in all EU states, and has also been introduced in Chapter V of the European Patent Convention.

The Biotech Directive has something to say about the isolation of gene sequences:

2. An element isolated from the human body or otherwise produced by means of a technical process, including the sequence or partial sequence of a gene, may constitute a patentable invention, even if the structure of that element is identical to that of a natural element.

Article 5(2) of the Biotech Directive

This would seem to impose almost no barrier to the patenting of naturally occurring genetic sequences. It is however important to remember that the other requirements for patentability still apply. In particular, the requirement for inventions to be non-obvious carries special weight now that the human genome is so well mapped.

Today, in 2019, we are well on the way to having a library of 100,000 genomes – just for the NHS (see the 100,000 Genomes Project – now 85% complete).

When the Biotech Directive was first drafted, we were still 13 years away from publication of the first (90% complete!) draft of the human genome!

The change in the state of knowledge in relation to the human genome is therefore likely to do the heavy lifting in relation to reducing the patentability of genetic sequences. A higher threshold for patentability is being naturally imposed by scientific progress. This is all part of the dissemination of scientific progress that is promised by the patent system.

At first glance it is slightly remarkable that the Biotech Directive has not been substantially reviewed since it was adopted. During that period there has been a revolution in the possibilities of genetic editing and in particular in personalised medicine. These developments bring about important concerns both in terms of the incentivisation of innovation, but also ethics. The ethical issues involved in the patenting of genes have caused substantial debate, which the patent system is not well equipped to handle.

(This topic is systematically covered in a forthcoming publication in European Intellectual Property Review titled Gene Patents and the Marginalisation of Ethical Issues by Dr Aisling McMahon. )

The Biotech Directive itself recognises that you shouldn’t leave ethical considerations solely to the patent lawyers (we’re far too busy anyway). Recital 44 and article 7 of the Biotech Directive palm off ethical considerations on the Commission’s European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies.

While the commission’s ethics brains have been busy working on AI recently, they are currently turning their minds to gene editing. Their report on ethical considerations in gene editing will be published in summer 2019, and is very likely to contain considerations relating to patentability. We will have to wait and see.

No patenting plants or animals

Let’s get back to our fish. Article 53(b) of the European patent Convention provides that European patents should not be granted in respect of plant or animal varieties. Why is this?

In relation to the prohibition on plant patents the EPO Boards of Appeal decision in G1/98, Transgenic Plant/Novartis II, explains this was largely to prevent double-protection under the UPOV Convention 1961, which gives rise to plant variety rights. This was a fortification of the position under the earlier Strasbourg Convention, which was ambivalent on the availability of patents for plant varieties. G1/98 concerned the use of genetic engineering processes to produce desirable traits in plants.

In the G1/98 decision Greenpeace acted as interveners, proposing that the prohibition on plant varitieies should be widely cast to capture those produced using genetic engineering, on moral grounds. The EPO disagreed vehemently, stating “there is no consensus in the Contracting States condemning genetic engineering”, considering instead that promotion of innovation in the field of genetic engineering was seen as necessary in Europe.

The Board of Appeal was clearly challenged by some unorthodox submissions on morality:

“the example given in amicus curiae briefs stating that polygamy cannot be allowed if bigamy is forbidden, although plausible at first glance, turns out to be less persuasive. In the same way as the ban on bigamy forbids marrying several persons, it is not permitted to claim several specific plant varieties. It is not sufficient for the exclusion of Article 53(b) EPC to apply that one or more plant varieties are embraced or may be embraced by the claims. “

G1/98

All of this is perhaps unsurprising. The EPO are poorly equipped to make moral judgments, and may be “institutionally pre-disposed to offer a narrow interpretation of the morality provisions” of the EPC (For extensive discussion, see the PhD thesis of Dr Aisling McMahon on that topic).

What is clear is that in deciding Transgenic Plants/Novartis II the Board of Appeal were not being guided by overtly ethical considerations of the type discussed in the last article, as considered in relation to landmines and gambling machines.

Practical Issues in patenting animals

The other key concern about patenting plants and animals is surprisingly mundane, and not to do with ethical issues at all. It is simply a matter of practicality. The European Commission notice (following the EPO Enlarged Board of Appeal decision in G 2/12 (Tomatoes II) and G 2/13 (Broccoli II)) explains that the same issue applies in relation to both plants and animals.

That notice quotes the European Parliament report preceding the biotech directive, that explains the issue as follows:

Breeding is a reiterative process, in which a genetically stable end-product with the required characteristics is attained only after much crossing and selection. This process is so strongly marked by the individuality of the initial and intermediate material that an identical result will not be obtained upon its repetition. Patent protection is not appropriate for such procedures and their products.

Explanatory statement to the ROTHLEY report, 25 June 1997 (A4-0222/97).

Therefore, contrary to what might be expected, patentability of plants and animals isn’t prohibited on the basis of any particular respect for living organisms, but just as a matter of practicality. This reasoning has always fallen a bit short in my opinion, failing to account for differing levels of consistency between generations. For instance, patents are allowed on clonally reproducing single celled organisms, but not on clonally reproducing plants.

Chilean “cushion plant” Pycnophyllum sp., which reproduces clonally

Oncomouse

While the exceptions to patentability for plants and animals are not based themselves on moral concerns, it does not mean that ethical issues cannot come into play when considering the patentability of animal inventions.

The most famous case relates to the Harvard Oncomouse. This type of laboratory mouse (mus musculus) was modified by Harvard researchers to carry an activated ‘oncogene’, i.e. a gene that massively increased the mouse’s susceptibility to formation of cancerous tissue. Without doubt a raw deal for the mouse, but a tool of incredible utility for cancer researchers.

The original oncomouse patent was handled very differently in the US, Canada and in Europe (WIPO article). The patent sailed through in the US, was rejected by the Canadian Supreme Court, and rattled around the EPO for years and years (granted – 1992, emerged from opposition in July 2004…). While the US patent excluded humans from the transgenic mammals claimed, the patent as amended in the EPO was eventually limited to lab mice.

At the date of the Oncomouse decision the Biotech Directive had still not been implemented in some European states (including Germany), forcing the commission to take the recalcitrant states to the CJEU for non-implementation. The implementation of the Biotech Directive was the end of the line for any arguments about an inherent moral barrier to patentability of higher or sentient organisms.

Since that date the use of transgenic organisms in research and healthcare has become commonplace. In 2015 the Beijing Genomics Institute even created micropigs developed using the TALENs gene-editing technique (sadly shelving their plans to sell them).

The EPO’s utilitarian approach in Oncomouse seeks to weigh the potential suffering to animals against the benefit to mankind. Given that micropigs do little to alleviate human suffering (in a medical sense at least) it would sadly seem unlikely that a patent on the same could be justified at the EPO.

Patenting Humans

There is one organism for which patent offices takes a stricter approach. Rectial 16 of the Biotech Directive explains the issue:

“Whereas patent law must be applied so as to respect the fundamental principles safeguarding the dignity and integrity of the person; whereas it is important to assert the principle that the human body, at any stage in its formation or development, including germ cells, and the simple discovery of one of its elements or one of its products, including the sequence or partial sequence of a human gene, cannot be patented…”

Recital 16, Biotech Directive

Recital 16 however goes on to say “these principles are in line with the criteria of patentability proper to patent law, whereby a mere discovery cannot be patented ” – i.e. luckily we already account for this under the discovery exclusion from patentability. The recitals do however go on to explicitly tackle the exclusion of human embryos from patentability.

The question of what is and is not a human embryo was considered by the CJEU in case C-34/10 (Brüstle v Greenpeace). The CJEU did not set a hard and fast line, instead stating that a stem cells from a human embryo would include any cells “capable of commencing the process of development of a human being“. This line has become increasingly blurred over the intervening years. In C‑364/13 (International Stem Cell Corporation v Comptroller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks) the CJEU held that the human embryo exception did not include the development of an ovum without fertilisation (i.e. parthenogenetically).

Further complications in the field have not been adequately addressed. There has been marked development in the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from other types of tissue by turning back the developmental clock. This has been welcomed for the removal of the majority of natural human embroynic tissue from research work. The issue now is whether there is really any difference between developmentally altered lab cell lines and naturally totipotent embryonic tissue. (For further discussion on this issue see Meskus et al. Embryo-like features of induced pluripotent stem cells defy legal and ethical boundaries (link)).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the EPO’s approach is unquestionably ‘innovation first’. The only situation in which ethics comes into patentability is in the specific provision for morality within the EPC. Even then, the EPO may be poorly equipped to deal with such concerns.

It takes immense time for countries even with the relative moral homogeneity of Europe to reach consensus on issues of patentability in relation to biotechnology. As a result, ethical considerations in patent law are likely to lag far behind the modern state of scientific research.

Next time

Having looked at the ethical issues relating to patentability, and in particular biotechnology, the next article will look at UN convention right to benefit from scientific progress, and consider whether that right is duly accounted for by intellectual property law.

If you have any comments or suggestions please do let me know – some of this discussion will feature at my presentation later this month at the Data Science and Right to Science Conference, and I’m always grateful for guidance on what makes for interesting content.

Attributions

Gene diagram: Thomas Shafee [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)];

Little piggy: Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-ND 2.0) licence –

https://www.flickr.com/photos/tambako/46524056954

One thought on “Ethics in IP, Part Two: Can I patent this fish?”