The decision of the Honourable Mr Justice Arnold was handed down in Glaxo v Vectura [2018] EWHC 3414 (Pat) (Bailii) on 13 December 2018. Given the deluge of legal developments in the world of patents in 2018 we should perhaps be glad that this is a quiet one legally speaking (the word plausible is only used once: Merry Christmas!).

Glaxo were successful at trial, as the learned judge made a finding of non-infringement for all five of Vectura’s patents, and had them all revoked for ambiguity-insufficiency for good measure.

Update – 2/1/2019: A friend pointed out that the result is going to be a major blow to Vectura. The Glaxo license was around 10% of their H1 2018 revenue at £8.8m. Not only will that cash stop coming, but Vectura will have to foot the costs of their legal expenses and most of Glaxo’s too.

There are a few interesting points of wider application:

- Judges are wise to follow-on patenting strategies in pharma and a well founded Gillette defence is a good way to keep this front and centre in the Judge’s mind.

- If you’re going to try and wriggle out of an arrow declaration by giving an undertaking not to sue, it will need to be a comprehensive undertaking.

- If you can’t demonstrate on the balance of probabilities whether or not someone has infringed your patent, there is no point having a patent.

Background

Glaxo ceased licensing IP Vectura owned that related to the formulation of powders for use in inhalers. These powders work by mixing an active ingredient with a carrier particle to improve dissolution and increase therapeutic efficacy. These formulations need to make efficient use of the active ingredient and achieve a therapeutically effective dosage release on inhalation. The patents in suit covered inventions relating to processes for the combination of active ingredient and carrier particles, and products made by those processes.

Gillette

Some interesting facts underlay Glaxo’s Gillette defence. Vectura had developed one of the key pieces of prior art, a patent called Staniforth, and had previously licensed that patent to Glaxo. When that patent expired Vectura were hoping Glaxo would continue to license a number of follow on patents, including the five in suit.

Glaxo’s case was that their own process was obvious over Staniforth and the other pieces of prior art. Glaxo therefore wanted to use the patent they had previously licensed to found a Gillette defence. It is clear that the team at Glaxo assessed the validity of the more recent Vectura IP and made a considered decision that the ongoing licence was commercially a poor choice, and that litigation would be preferable to the terms offered.

Arnold J didn’t find that any of the Vectura patents were obvious over the prior art. He did however find that the process used by Glaxo was obvious over each piece of prior art. This meant Glaxo had successfully established their Gillette defence. This defence is unusual for an innovator company in pharma. Here the declaration of obviousness only relates to a method of formulation, rather than any of the active ingredients. It therefore doesn’t matter as much to Glaxo whether other companies will now feel safe to copy their formulation method.

Arrow

Glaxo’s request for an arrow declaration was originally shot down by His Honour Judge Hacon, sitting in the High Court, before being reinstated in the Court of Appeal by Lord Justice Floyd in decision [2018] EWCA Civ 1496 (not 196 as mistakenly stated in the HC judgment) (bailii). Good job it was reinstated, as it turns out.

Glaxo’s formulation process was held to be obvious at the priority date of the patents in suit. As the judge said, this is a necessary but not sufficient precondition for the grant of an arrow declaration. There must be a useful purpose beyond that declaration of obviousness. Glaxo’s case on this was that they needed commercial certainty and the knowledge they would be free from further interference by Vectura. Glaxo alleged Vecturas to be pursuing new patents by simply re-phrasing the essential magensium stearate formulation technology previously licensed by Glaxo.

Vectura’s case was that the declaration would serve no useful commercial purpose and should not be granted. In particular they objected to the exact forms of the two declarations ([245] and [246] of the judgment). Vectura also said that the declarations would serve no purpose as they would give an undertaking to similar effect.

Back when the striking out of Glaxo’s claim for arrow relief was being considered by HHJ Hacon ([247] of the Judgment oddly says this was Glaxo’s application to strike out its own arrow relief?) Vectura offered an undertaking to the Court:

[Vectura] will not assert in the UK any patent applications from within the Non-Assert Patent families (as defined in the agreement between [GSK] and [Vectura] dated 5 August 2010) with a priority date on or after 30 November 2000 which subsequently proceed to grant against the processes described in the … PPD … and Products identified as being made directly therefrom ….”

Glaxo objected to the form of this undertaking, saying it didn’t go far enough. Glaxo identified an additional patent family being pursued by Vectura that would not have been covered by the undertaking. Arnold J found this persuasive and determined that the declarations sought would give Glaxo additional certainty regarding their freedom to operate, and made a declaration in the following form:

“A declaration that the Claimants’ Processes described in the Annex A [which is the same as the PPD save for the fact that the particular Comil model (U5) is deleted] and the Claimants’ Products which are direct products of those Processes (and save for the active ingredients therein) were obvious as of 30 November 2000 or at any date thereafter.”

Impossible to Infringe

Vectura failed to prove that Glaxo infringed their patent. They were unable to prove by their testing that the Glaxo product or process fell within the claims.

This is unquestionably a rather unfortunate situation to be in. It is a helpful reminder that burden of proof is on the party alleging infringement, but perhaps more importantly it is a reminder not to include supposition in claim language. Arnold J hits the nail on the head at [177]:

The starting point is that the Patents contain very little guidance indeed as to how the skilled person is supposed to determine whether a process has produced composite active particles in which the additive particles are fused to/smeared over the active particles so as to form a coating.

The essential problem is that the patentee has no real knowledge that the process disclosed fuses or smears particles in the manner claimed. It may well be supposed that is how it happens: perhaps it follows from the forces applied in mixing, or can be surmised from the clinical efficacy of the formulations once produced. Unless it can be objectively tested it should not be included in the claim language. No doubt it was hard graft to get the patents in suit granted given the prior art, but the claims do seem to have overreached.

In looking to demonstrate infringement in a claim of this value the patentee will most likely put in a great deal of resources. That work will likely exceed the standard of ‘undue effort’ beyond which the patentee would be considered not to have properly disclosed its invention.

If the patentee can’t prove infringement it is undoubtedly bad news for ambiguity-sufficiency, i.e. “I can’t tell if I am performing the invention” type sufficiency. That was the case here: Arnold J determined the patents did not enable the skilled person to determine whether a product or process is within the claims without undue burden. The patents therefore could not be valid.

In coming to this conclusion Arnold J relied on the summary of the law of Mr Justice Birss in one of the Unwired Planet technical trials, which is a helpful endorsement of that summary of the law.

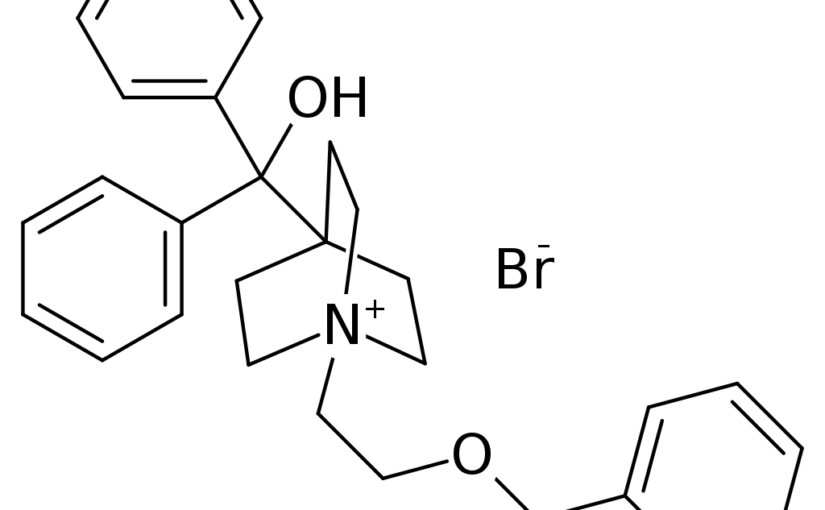

Header image: Ed (Edgar181) [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons