On 29th January 2019 the Hon. Mr Justice Henry Carr handed down his judgment in the case of Garmin (Europe) Limited v Koninklijke Philips N.V. [2019] EWHC 107 (Ch).

The aim of this article is to look at how the parties’ cases in Garmin v Philips appear to have changed during the course of litigation, and to think about why that often tends to be the case in litigation, and in particular for patent litigation. As Henry Carr J says in his judgment: “Cases change during the course of litigation, which may mean that issues once seen as important no longer matter.”

This post will look at five reasons why cases can change between issue and judgment. Next time a client asks what their percentage chance of success at trial is, bringing up a few of these points might help explain why 31% to 83% is a reasonable range for you to give them.

Background

A helpful summary of the issues in the Garmin v Philips case can be found at the EPLaw blog. In short, the case related to wearable fitness trackers and a whole host of major and minor functionalities that are inherent to those devices. From big picture features like tracking and recording pace, to more minor features like reducing music volume when getting feedback from a device.

In procedural terms, Philips found itself on the end of a revocation action brought by Garmin against its patent EP (UK) 1,076,806 B1 and subsequently counterclaimed for infringement by seventy-three Garmin products. It was a Pyrrhic victory for Philips as while the patent was valid and infringed as conditionally amended, the aspects of the patent that went to the more valuable core functionality of the Garmin devices were held to be obvious.

The first of the five points we will look at is the effect of assessing inventive step and sufficiency at the priority date of the patent.

1) Looking to the past

It’s important to remember at this point that Garmin wasn’t always a purveyor of trendy wearable tech: the company was not that long ago in a pretty bad place, heavily invested in the rapidly imploding car GPS market that was taken to the cleaners by the advent of smartphone navigation apps – turn-by-turn navigation only came to the iPhone in 2012! Garmin undertook a successful pivot from navigation devices marketed at sailors and serious outdoors types to the modern watches that adorn the wrists of both decathletes and desk-athletes. (sorry)

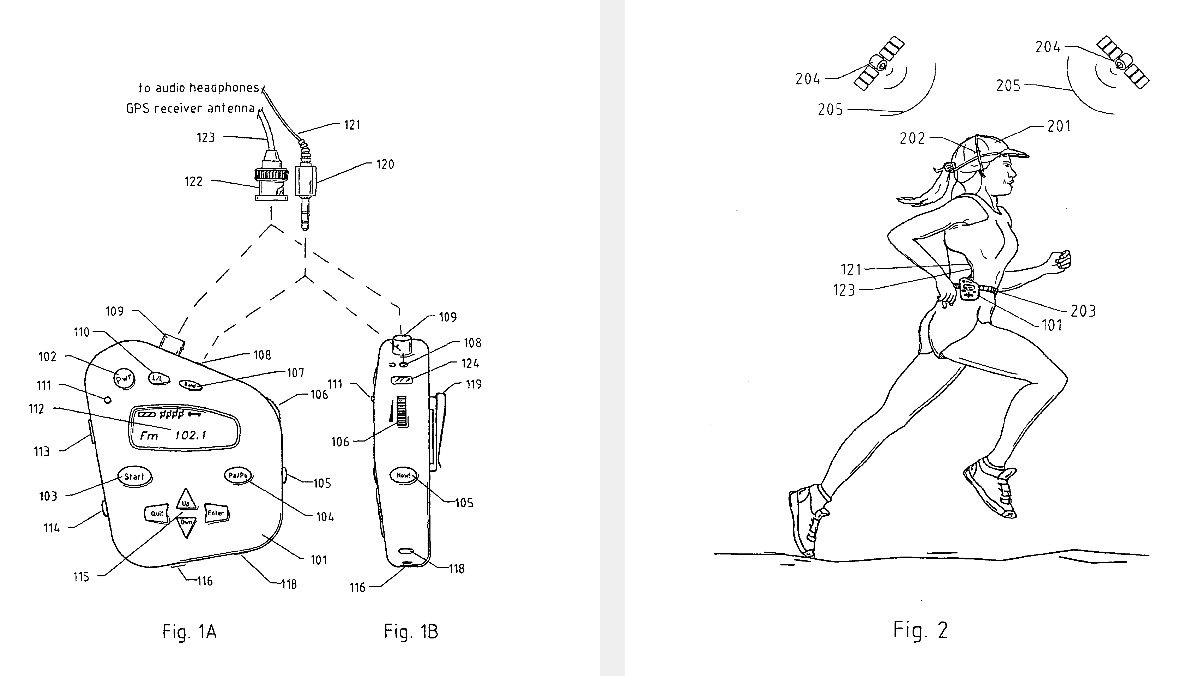

The EP1076806B1 patent holds a priority date of 1998, and has a company called Sportbug.com, Inc. as its original applicant on the EP register. This company appears to have been a vehicle for two researchers called Gary Root and Frank van Hoorn, who are mentioned in a 2001 NY Times article about nascent GPS technology. The NY times describes their workout tracking invention as being “built into a personal radio with headphones, and could be linked to a computer so the data might be downloaded.”

Patent law nerds only: Incidentally, no issues of entitlement or priority appear to have been argued – perhaps surprisingly given the common issues arising from the unfortunate US-centric habit of backdating assignments of the right to claim priority, which doesn’t pass muster in Europe – see Edwards Lifesciences v Cook. You can see the US assignment history here, which appears to show that the original inventors only assigned their rights in the invention to a company called Liquid Spark, LLC on 18th June 1998, almost two months after the application for the EP806 patent was filed on 26th March 1999. There must therefore have been some other assignment (in a contract of employment maybe) that transferred the right to claim priority to the EP applicant from the original inventors.

You can see the state of technology at the date of the application from the figures that were included in the patent:

Many of the issues in a patent action are assessed at a date that can be a long time in the past, and it takes time for a settled understanding of the situation as at the date of priority of the patent to take place. Similar historical issues can occur in other claims, for example in relation to historical ownership of goodwill prior to filing of a mark, or the intentions of the parties before agreeing to a contract.

The consequence of this is that when issuing a claim it will almost always be on the basis of incomplete information. More will always come to light over time, and alleged infringers may often take some time to find out how the alleged invention was really perceived by those in the art at the relevant time.

2) Ask the expert

Tied into the first issue is the question of expert evidence. Finding an expert that was practising in a specific field twenty years previously will always be a challenging task (though should become easier over time thanks to the work of LinkedIn, Arxiv, Github and other accidental historical repositories of expert info).

In Garmin v Philips one of the major changes in the case was Philips abandoning its reliance on the patent representing a Schlumberger type invention: i.e. one which arose out of the combined expertise of two previously independent fields. Philips’ case was originally that a GPS specialist was concerned with navigation at the priority date and would not have appreciated the possible application of the tech to athletic performance monitoring.

This change in Philips’ case appears to have come about after the exchange of expert reports (see [17]) and therefore its expert evidence was advanced on the basis of two non-communicating experts working in different fields. Having given up on this legal distinction Philips went on to accept that claim 1 of EP806 as granted was obvious over the main prior art citation (“Schutz”), which related to using GPS to track physical activity and was published in the European Journal of Clinical Medicine.

Philips’ expert came in for some criticism in Henry Carr J’s judgment, not for lack of effort or inexperience in the areas in which he had worked, but for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Perhaps more accurately, for not being in the right place at the right time – he just didn’t know enough about GPS. The Judgment explains that it became apparent in cross-examination that Philips’ expert had almost no contemporaneous personal experience of the GPS industry or ‘athletic monitoring’, his experience instead being found more in the ‘wearable tech’ side of the equation.

While it is impossible to know what role the expert witness had in pushing Philips’ case in a Schlumberger direction, that position caused an inherent vulnerability. If your single expert can give true expert evidence as to both of the arts alleged to have been combined in the invention, then your case on invention by unification of disparate fields seems weak. On the flip side, if you run a Schlumberger type case with a single expert and are unsuccessful, on your case as to the skilled person, then your evidence as to obviousness is fatally undermined. Of course this is easy to say with the benefit of hindsight – Henry Carr J didn’t linger on the fact, noting that while the identification of the skilled person did compromise Philips’ position “the case has moved on since service of the expert reports”.

Experts at trial

As the saying by W.C. Fields goes, “never work with animals or children“. If Mr Fields had been a patent litigator no doubt he would have added expert witnesses to his list. As discussed above, expert witnesses can be an undesirable source of unpredictability in Court. Certainly when it comes to advising on prospects of success in any patent claim retention of a qualified expert witness is an essential requirement. The essential problem with expert witnesses is that they sometimes say things that aren’t very helpful to your case.

This is, contrary to popular opinion, A Very Good Thing. It means that the principle of independence is working, and that Judges are being given the unbiased information that they need to come to their conclusion. As we can see at [178] of the Judgment Garmin was forced to modify its case on conditional amendment Claim CA2 in response to concessions by its expert in the box, who (very sensibly) accepted that the claim feature in relation to music volume reduction during audible exercise feedback would not be satisfied by the user manually turning down the volume on their walkman.

Expert witnesses are therefore a major factor in how cases change both before and during trial.

3) Time, Money and People

As Henry Carr J point out in his judgment, a firm of solicitors running a patent litigation case is liable to bring to bear considerable resources, and unearth materials and information that might never otherwise have come to light:

“[The Claimant’s expert] then gave evidence as to common general knowledge by reference to extracts presented to him from a search of magazines and other publications conducted by Garmin’s solicitors, Powell Gilbert, at Mr McKnight’s suggestion. As one might expect from a highly skilled team of lawyers, this was a very thorough search, and covered sources of which Mr McKnight fairly accepted at [55] of his first report that he was not previously aware.”

Of course, there will also be material changes to the case that result not from time spent in a search for documents, but from simply thinking about the case.

Amendments

This is particularly true with the question of amendments, which can completely change the game in patent litigation. These generally require a certain amount of ingenuity, and generally there is a real benefit to some collaboration across counsel, solicitors and patent attorneys in coming up with something effective.

In Philips one of the conditional amendments sought saved the patent: Claim CA2. The functionality claimed (the volume reduction feature described above) is a comparatively minor aspect of the functionality of the devices alleged to infringe, nevertheless, for a patent in force this can still lead to a commercially valuable injunction, and while an issue based costs order would seem inevitable, having an infringed claim at least gives Philips good grounds to say that it was in fact the overall winner of the dispute.

Additional Prior Art

Another issue that can come to light with appropriate application of resources is prior use. By way of example, in the case of Blue Gentian v Tristar (bailii) in 2013 no issues of prior use arose. That same patent (UK Patent 2 490 276), for a flexible garden hose design, was litigated between different parties at the start of 2019, but this time with an alleged prior use by the inventor (incidentally, a very interesting judgment is awaited on that case, including consideration of a Formstein defence to infringement by equivalents). That just goes to show the difference that a bit of digging around can make.

4) Keeping it Brief

The UK Court reforms have in general created a considerably tighter environment for litigation. Just think about the fact that the 1971 patent litigation case of General Tire v Firesone Tyre & Rubber ran for 29 days … in the Court of Appeal. Keep in mind that case was for a patent for a composition of rubber for use in car tires: in the High Court today it would be on for 2 days, and would probably get put in the shorter trial scheme.

In contrast, Philips v Garmin was on for 5 days, including closing. Somewhere along the way something has changed for the better. However, this more efficient approach isn’t without consequence. In the UK Courts (as compared to the EPO for example) it is vitally important to only run the most appetising arguments. A very vulgar metaphor relating to cupcakes on plates is often peddled to make this point, but I shan’t repeat it here because my blog will get taken off line by half the web-filters and firewalls in London. The gist is that if you have one bad argument it can raise doubts about the logic behind all your others.

Equally, failing to make concessions on issues like the identity of the skilled person can make it look like you have serious doubts in relation to other aspects of your case. Arguing for a stupid skilled person is one easy way to make it look like you can’t defend your patent on a reasonable obviousness case.

Philips v Garmin is a good example of where helpful compromise can save Court time and bolster the credibility of remaining arguments. The Judge helpfully sets out at [4] the issues compromised on before and during trial:

- Garmin did not pursue various of its prior art citations, or only pursued certain prior art in the event that its collocation attack was successful.

- Garmin did not cross-examine in relation to the evidence of infringement and did not rely upon any evidence as to non-infringement.

- The dispute as to the identity of the skilled person evaporated, and Philips no longer advanced the submission that this was a Schlumberger-type invention.

- Philips accepted that claim 1 of the Patent was not only anticipated by, but also obvious, in the light of one of the prior art citations (Schutz Y and Chambaz A, “Could a satellite-based navigation system (GPS) be used to assess the physical activity of individuals on earth?”, European Journal of Clinical Medicine (1997) 61, 338-339) (“Schutz”)

For points 1 and 2 these appear to have occurred by the time of trial, but subsequent to exchange of skeleton arguments. In relation to number 4 in particular the Judge noted that the concession arose in the oral closing of Philips’ counsel, Dr Brian Nicholson.

Concision: A team effort

It is worth mentioning that the separation between barristers and solicitors in the UK system also lends additional advantages in trimming the issues in a case. Whether a drive by counsel to simplify arguments and drop unattractive points is driven by a fear of judicial wrath, or instead by a powerful sixth sense as to innate jurisprudential merit remains a matter for debate. The two may in fact strongly coincide.

Regardless, there is definitely an advantage to having someone who has previously been less involved take a deep dive into a case closer to trial, in that their perspective can more closely match that of the Judge. Speaking from experience, working on the day to day of a case can definitely make it harder to spot the broader arguments that might ultimately be the most attractive in Court.

Certainly earlier in a case the costs consequences of litigating additional issues unsuccessfully can also lead to a party changing or even discontinuing part of their case. This is perhaps less of a motivation in patent litigation where the amounts at stake are often so high. While by the time of trial the costs consequences of running unsuccessful issues are unavoidable there is a very real benefit to a party’s credibility. This brings us neatly to the fifth and final point.

5) Leave it to the Judge

The UK Courts have a great reputation for judicial expertise, and active case management is an approach that has been very successful, if occasionally disconcerting to those being managed. Many of the Judges in the Patents Court are not strangers to giving parties a steer as to the issues on which to focus their attention, in a manner that would be quite unorthodox in some jurisdictions. For example, in the recent case of TQ Delta v Zyxel [2019] EWHC 562 (Ch) (Bailii) it would be fair to say that during closing Henry Carr J gave Zyxel a fairly good steer as to the fact that TQ Delta’s unorthodox argument on the ‘430 patent didn’t hold much hope, advising counsel to “expect more resistance” in relation to the ‘268 patent.

This kind of judicial intervention should be welcomed. Judges are never going to be short of opinions from the first moment they have their hands on a case. Withholding their inclinations from the parties is liable to be counterproductive and to waste the Court’s time on arguments and issues on which there is little prospect of success. This is of course a fine line on which to balance, as to step too far and leave a party feeling that their case has not been heard would be completely inimical to the principles of our justice system.

Balancing the need to make best use of the Court’s time with the need to ensure parties are able to put their case is a tough ask, but one that the UK’s judges seem to do admirably well. Whether it’s the more obvious cues: “and if you were to be successful on that point what effect would that have on…“, or the more subtle ones, such as the Judge’s pen slowly drawing to a halt, the UK’s adversarial and hearing-centric court system lends itself well to a narrowing of the issues.

Conclusion

Given the scope for litigation to change tack it is sensible to advise clients from the outset of the factors that are liable to change the course of litigation. That is especially true for issues that are within the control of the parties, such as selection of experts.

For other “black swan” type issues the best that can be done is to remain flexible and to be prepared to rapidly adjust a case to make the best of a changing situation.

Credits

Header image – Matti Blume (MB-one) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]